“This is only the beginning.”

The introductions to each faction in the world of Dune are brief, yet stimulating. While we learn important pieces of contextual information about each through narration and dialogue, sensory details do much more of the emotional heavy lifting for us. Denis Villeneuve’s cinematic adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel relies heavily on all aesthetics of the medium — visuals and audio — to communicate how we’re meant to feel about each group.

We do not identify the Harkonnens as villains or feel tense when their soldiers first appear onscreen simply because Chani calls them the Fremen’s “oppressors” in voiceover narration. We feel tense because of the dark, threatening, buglike look of the soldiers’ desert attire, which completely shrouds their faces from our view — and because of the gasping wind and rapid heartbeat that pulsates on the soundtrack as Chani speaks about the Harkonnens’ cruelty to her people, and the intense, erratic drumbeat that loudly accompanies a sequence that introduces one of their military’s leaders as he gazes out over their menacing machines.

That same fearsome, erratic drumbeat plays the first time that we see a Fremen emerge out of the desert sand itself to assassinate a Harkonnen soldier in slow motion, too; this visceral ferocity plays in stark contrast to the first images that we see of the Fremen sitting calmly in the sand, bright blue eyes piercing through the thick desert dust. Through this aesthetic contrast, we learn that they are strong, resourceful, and at one with the desert — stoic, but swiftly violent when necessary.

We first meet the leader of their oppressors, the Baron Vladimir Hakonnen, a few scenes later. His introduction is prefaced by a statement in a training session in which the Atreides House Warmaster Gurney spits at Paul, “You haven’t met Harkonnens before. I have. They’re not human; they’re brutal.” This sentiment sets our expectations for who the Harkonnens are, and then immediately after, we see their dark, ominous, futuristic home world, Geidi Prime, accompanied by musical score that sounds like a blend of strings wailing and industrial machines pulsing. The Baron himself is a massive lump of a man, pale and fat and shrouded in fog. His look and his voice — deep, commanding, drawling — are both unnerving. He rubs his sweating, bald head with his hand; his behavior in this scene harkens back to Marlon Brando’s performance as the unpredictable, violent recluse Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. The pop culture reference is a subconscious indicator to us that the Baron is an unhinged leader.

The Baron doesn’t get a lot of screen time in Dune, but when he does, he comes across as a disturbing, mysterious, and menacing force. There is unsettling discord on the soundtrack as he rises into the air to an unnatural height, robes flowing beneath him, while proclaiming that the planet gifted by the Emperor to the Atreides family is, “my desert. My Arrakis. My Dune.”

His mighty presence, established via startling aesthetic choices, lingers over the entire movie in spite of few scenes centering around him.

Bold style imbues the film with tension even when the villain is out of sight.

In contrast, our hero gets a moody, foreboding introduction that elicits trepidation more than strength. We first see Paul Atreides in close-up, fast asleep; raindrops patter on his bedroom window, and the reflections shroud his face in shadows that resemble tears. Villeneuve cuts to a wide shot of the bedroom in which Paul, shirtless and vulnerable, sits up, hunches over, and stares at the ground as melancholic music plays on the soundtrack. The future of House Atreides is haunted by nightmares — his introduction poses more questions than answers about his capabilities.

When the herald of the change greets Paul’s father, the Duke Atreides, in a formal ceremony granting the Atreides family command over the desert planet Arrakis, the Atreides clan accepts the call as an honor. But the buglike attire of most of the congregation before them, and the deep, pulsating bass sounds and chanting female voices on the score make us feel uneasy. It’s clear from sonic and visual cues that this isn’t exactly a joyous occasion.

The Duke Atreides, however, speaks eloquently and proudly, stating clearly to the assembled crowd that “there is no call we do not answer. There is no faith that we betray.” His pride and idealism will be his undoing.

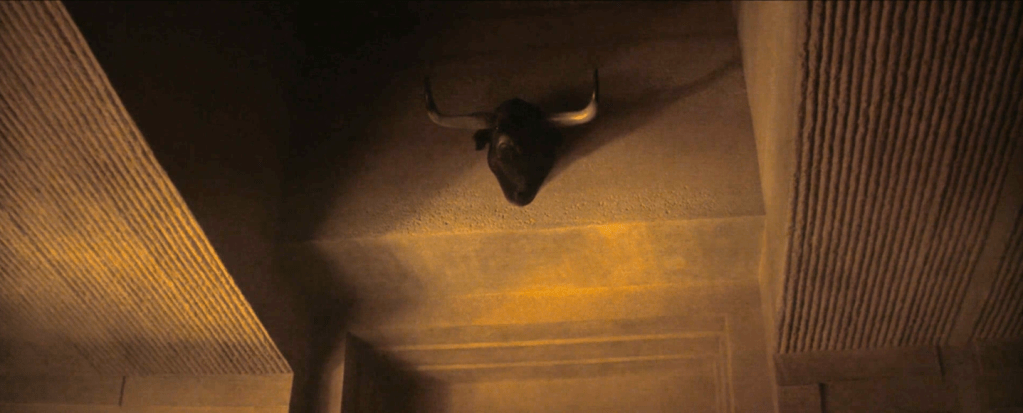

Villeneuve uses a recurring visual metaphor to consistently remind us of this familial character flaw. In an early scene, Paul and his father visit Paul’s grandfather’s grave. A bull and its fighter are etched into the gravestone. “Grandfather fought bulls for sport,” Paul exclaims to his father later in the scene as justification for his request to take risks and personally scout Arrakis.

“And look where that got him,” the Duke replies, implying that a bull killed the former head of the House.

Throughout the film, we see the head of that murderous bull before the scene of Paul’s ‘test’ at the hands of the Reverend Mother, carefully packed up for transit to Arrakis, in the background of the great hall in which the Duke’s wife Lady Jessica selects a housekeeper, and finally high above the room in which the Harkonnens enact the final stage of their coup.

The overt visual symbolism creates tension and thematic unity without words.

As in any other movie, we learn much about characters and their world through dialogue and action — there is a thrilling scene in Dune which serves a dual purpose: world-building, and cementing the values of the Duke Atreides for us so that his story becomes all the more tragic. In this scene, the Duke executes a bold, daring aerial rescue operation for spice harvesters trapped in the desert — and we see the power of the infamous sandworms of Arrakis for the first time.

But mood — conveyed through the interplay of visual and aural cues — drives more of our emotional reaction to the film than traditional dialogue and plot elements do.

When the Bene Gesserit first arrive on the Atreides’ home planet of Caladan, they emerge from their ship, which resembles the head of a locust, shrouded in black robes. Rain pours down on them in the darkness of night, wind whips their robes erratically behind them, and harsh female whispers chant aggressively on the soundtrack.

We immediately distrust them. Even though we know loosely that Paul’s mother has been trained by them and that Paul is learning their skills as well, something feels off; by the time Paul comes face to face with the Reverend Mother for his ‘test,’ aesthetics have made us feel like the Bene Gesserit have to be up to no good.

The details and design of all of the environments and creatures, too, communicate volumes of lore to us efficiently. The attention to detail in the cracks of the skin, huge size, and fearsome bristles of the sandworms shows us what it takes to survive in the wilds of the Arrakis desert — and, by proxy, how strong and resourceful the Fremen truly must be. The designs of the temples, underground caverns, and halls in Arrakis speak to a deep, hallowed history as well — their ancient look and feel make all who occupy them by outsider decree feel like intruders, even if the temples and halls are their homes by legal right. And, there are sonic cues — musical motifs, and unsettling, carefully constructed sound design — which permeate every scene and give us insight into the culture — and feeling — of this alien world.

The entire second half of Dune is a violent coup and its related battles, and the world is so vast with so many groups of characters that these distinct stylistic cues for each become not just interesting but essential, because they orient how we’re meant to be feeling and give us a clear frame of reference for what people stand for in this somewhat sprawling narrative.

All of the stylistic and design choices support the plot, but the intense precision of the choices and the sensory overload that is so often packed into scenes here does something more than that as well: they make Dune a captivating, immersive film that you truly experience, not just passively watch. Aesthetics pull you in and occasionally overwhelm you — and that sensory overload is part of the storytelling methodology that keeps us hooked.