“You’ll be grown before that tree is tall.”

Mrs. O’Brien receives a telegram at her front door. The camera rotates around her face until we see her darkened to a near silhouette in front of the floor-to-ceiling windows of her Waco, Texas home. The camera then follows her through her living room as she opens the Western Union envelope. She pauses. There is a jump cut in the edit, and suddenly she is no longer standing, but sitting in a chair, expression shocked, telegram in hand. We cannot read what it says. She drops it. There is another jump cut. Now, her eyes are glistening and she is breathing heavily. The handheld camera shifts from an eye-level close-up to a high-angle, canted wide shot as she stands. She reaches out toward a table for support and gasps while the handheld camera attempts to frame up a wide shot. The camera never settles before the scene cuts to a new environment. The last few frames of this vignette are out-of-focus, haphazardly angled, and shaky. Her exclamation of “Oh God” merges with the roar of a propeller plane’s dual engines on the audio track.

We never see what the telegram says.

We then see a shot of a man’s arm waving at the propeller plane. The sun flares the lens, then the handheld camera composes a profile close-up of the man. Mr. O’Brien clasps one hand to his left ear to dampen the ambient noise; we see his wedding ring. The camera then rotates around again, settling slightly below his face. He speaks into the phone, but we cannot hear him. His expression freezes on shock, then despair. A jump cut to another handheld shot occurs, which follows him while he strolls in a daze on the airstrip. He bends over, struggling to support himself. The sun sets on the airfield.

We can imply, but it not explicitly shown or mentioned, that Mr. O’Brien is on the phone with his wife. We do not hear what they say to one another.

We first see her grief, then his.

The next thing that we see is a crane shot of winding tree branches interrupted by flashes of a sunset. A church bell tolls on the soundtrack. Malick cuts to a handheld, profile tracking shot of Mrs. O’Brien walking down a suburban street, crying, with her arms folded. The camera rotates around her until it reveals Mr. O’Brien walking behind her. She turns around. Malick abruptly cuts to the reverse shot on her. She quickly turns around again, completing a 360-degree motion that makes the cut to this reverse shot feel like a jarring jump cut. Mr. O’Brien then enters the frame. She clasps her hand to her mouth; his actions are more stoic. He gently touches her shoulder. We again see his wedding ring.

The edit becomes a disorienting montage:

An empty bedroom. Mr. O’Brien on his knees next to a window, eyeglasses lying on a bench. Mrs. O’Brien standing next to a window with half-open blinds in an unidentified room, her eyes glistening. Handheld shots of paintbrushes and a guitar. A quick shot of a young boy playing a guitar, followed by a rotating shot looking up from the ground floor of a church at the beautiful panes of stained glass in the ceiling above. “My hope… my God…” whispered in narration, barely audible above sparse organ music, as presumed but unidentified friends and family console Mrs. O’Brien in the same neighborhood seen before. An upside-down shot of children playing in the streets — but we only see their shadows. The organ music swells.

Director Terrence Malick isn’t interested in giving us full scenes to become dramatically invested in. He’s interested in showing us flashes of raw emotion. When the boy’s grandmother tries to offer words of reassurance to Mrs. O’Brien, Malick lingers on the younger woman’s face as she hears unhelpful words, “You’ve still got the other two.” Mrs. O’Brien’s nostrils flare, and her eyes twitch. She tries to hold back the oncoming tears. The scene cuts away and the older woman’s misguided words become narration. Malick frames a shot from outside of the home looking in through the floor-to-ceiling windows. Mr. O’Brien squats on the floor in despair. We see Mrs. O’Brien’s faint reflection in the windows in front of him, strolling in the yard. The camera pans to reveal her as Mr. O’Brien stands and exits the living room, then follows her until the sun flares the lens. Angelic voices swell on the soundtrack; Malick cuts to a close-up of Mr. O’Brien softly speaking what sounds like an existential confessional in the yard. His voice is filled with regret; tears glisten in his eyes.

Malick doesn’t linger for long.

We can generally intuit what happened, but Malick is not interested in the specifics of the young boy’s death, nor even the specific impacts that it has on the O’Brien family. Over the course of seven minutes, Malick crafts a sequence vague and experimental enough that it transcends the specifics, hinting at the essence of grief itself.

The handheld camera’s shakiness and the edit’s jump cuts mimic the characters’ emotional instability. The way in which Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien are blocked within scenes indicates that even though they are together, their processing journeys are entirely separate. The words of others do not help, so they are mostly left unheard.

The edit is impatient. Every moment is selected for emotional effect and most are spliced to the point of abstraction. There are enough specifics noted throughout to resemble a plot and provide character motivation. But the sequence is more interested in the ideas and raw emotions. We see despair. Cut. Regret. Cut. Anger. Cut. Disassociation. Cut. A shot of nature allows us to briefly process our own feelings. Cut. Separation. Cut.

The entire first third of The Tree of Life is structured this way. Malick moves fluidly through time and space over the course of 40+ minutes to introduce us to the characters and concepts that he wants us to ponder while we absorb the comparatively straightforward sequences that comprise the middle of the film.

A single shot of a supernova in space separates the aforementioned scenes in 1950s Waco, Texas and a lengthy montage that introduces us to the adult version of Jack O’Brien, who lives and works in a hybrid construct of a Texas city (scenes were filmed in both Dallas and Houston). Malick shows Jack and his wife at home, occupying the same spaces but never connecting with one another — she walks through one portion of the home while we see, through windows, Jack pacing in another; she sits on one side of their bed facing the wall while he wakes up facing the other. In the kitchen, he stares at a blue candle, lost in thought; she stares back at him, but doesn’t say a word.

Are they fighting? Are they grieving? Malick doesn’t say, nor does he let them give us any hint — they are treated as models: stand-ins for our own emotional projection.

The mash-up of city skylines removes us from thinking of the setting as a singular place — again placing us in the realm of abstraction. Flashy, dramatic images of skyscraper interiors and exteriors position us not in a specific city but in the idea of a city. We see Jack saying vague things that sound like business talk on a phone. He points at blueprints, and sits in meeting after meeting in a variety of conference rooms. He doesn’t say much. There’s no spark to his expression. We don’t quite know what he does for a living — but that’s the point. Malick doesn’t care so much about what the man does, so much as he wants to convey that Jack has “a dead-end corporate job.”

This sequence introducing Jack as an adult jump cuts between three time periods and physical spaces: the present, at his home and his work; the past, in Waco, where we see flashbacks of him with his deceased brother; and a future, in what seems to resemble heaven or limbo or some sort of ancestral plane, where Jack wanders adrift in a desert and runs his hands across boulders.

The adult Jack is less a character than a generic, abstracted stand-in for a type of person: a man stuck in the past, detached from the present, hopeful but pessimistic that he will have a more deeply connected future.

After introducing us to the film’s main characters, Malick shifts The Tree of Life into an entirely different realm.

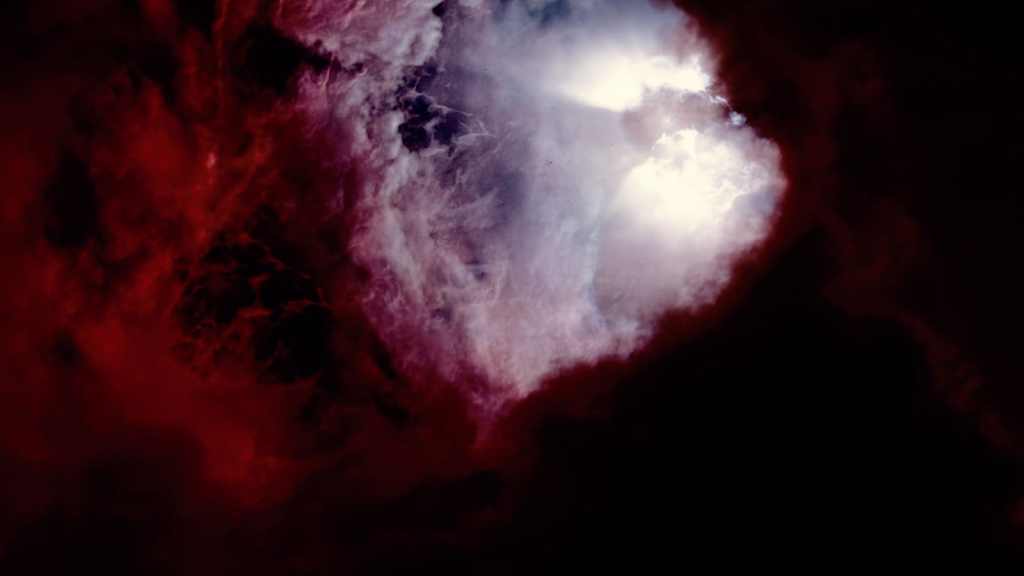

Nearly 20 minutes of montage convey nothing less than the birth of the universe itself. Operatic voices cry out in song while we watch the cosmos turn, stars expand, steam erupt, magma boil, and cells divide. Dinosaurs appear on the shores of beaches on a young Earth. A predator spares the life of its prey. An asteroid rotates slowly through outer space. From space, we see magnificent shockwaves ripple across the ocean as it hits the Earth.

This sequence completely changes the way we view the rest of the film by contextualizing the drama and pain of the O’Brien family in the grandest possible scheme: that of existence, space, and time itself.

We see the O’Brien’s grief, and it feels so deep. We witness it beside the explosive birth of the cosmos, and they feel so small.

Voiceover narration provides a few whispers of guidance as to what we are meant to take away from it all — such as when Mrs. O’Brien muses on a teaching she once learned from nuns: “there are two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace.”

Without the birth-of-the-universe sequence, the theme to be construed from that could be: life is often full of suffering, and the way out of suffering is through grace and love.

With this sequence, however, the theme becomes more spiritually nuanced: we are but a tiny speck in the vastness of the universe, a small and seemingly insignificant part of the unknowable evolution of consciousness through time. Our suffering is deep but fleeting… and the only way to make sense of that suffering and the chaos of life is through grace and love.

Because of the narrative framework partially established by this sequence, The Tree of Life begins to feel less like a traditional drama and more like a call to faith — Christianity, if any, in the specific; non-denominational in the abstract.

The middle of the film slows things down. Sequences henceforth, until the film’s finale, take place almost exclusively in Waco in the 1950s. These scenes are longer, less choppy, and seem to be roughly chronologically arranged. But chronology, like the specifics of Jack’s profession and his brother’s death at age 19, are not of primary interest to Malick. His interests, instead, are grander: perception, emotion, and the human experience, both good and bad.

Jack and his peers play and fight and go to places that they should not go. Mrs. O’Brien loves them to the point of coddling; Mr. O’Brien pushes them to the point of authoritarianism.

The camera energetically glides after Jack and his friends as they play in the streets and hide behind a tree; heroic music plays on the score, and their lives feel triumphant.

A handheld camera and dramatic tension give a different scene, in which Mr. O’Brien loses his temper on his family at the dinner table, a more chaotic feel.

Many scenes are shot from young Jack’s point of view. In one of those scenes, the camera follows young Jack as he strolls around his house at night, and we see through the windows, from his perspective, his parents angrily fighting with each other inside of their kitchen. Malick shows us his expressions in close-up, and we can interpret them as fear or anger or anxiety. We do not hear what the fight is about. It does not matter. Rather, what matters is what the scene represents: the fact that children see and hear things that they are emotionally unequipped to understand. The way that the scene is shot and edited places us in that same position — we cannot hear the fight, and so we cannot understand.

This is not much different from Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien’s own struggles to comprehend their own incomprehensible grief. Even though they go through the same tragedy, their words cannot console each other, and they must process their grief alone. Even as adults, our own emotional and existential understanding in extreme circumstances can only go so far.

On its own, the middle of The Tree of Life is a beautiful slice-of-life movie. It explores the tension between a loving mother and an authoritarian father, the ways in which a child comes of age, and the ripple effects that grief can have on a family. It examines the joys and confusions of childhood and adolescence. It finds profundity in moments big and small.

But positioned between the aforementioned experimental sequences and the dreamlike finale, in which all lives converge on a surreal, spiritual plane, this slice-of-life narrative becomes something much more philosophical. Altogether, the film asks us to ponder our place in the universe, and gently consider living a life devoid of selfishness and filled with grace. It decrees, in all of its abstract ways, that we may be able to find solace in even our deepest suffering through generosity, forgiveness, and love.