“A war’s no place for children.”

About an hour into Ivan’s Childhood, twelve-year-old Ivan hoists a bell to the ceiling of a dark bunker. He pulls a knife out of his belt and slips into the shadows. Director Andrei Tarkovsky cuts to a ground-level shot of the young protagonist as he army crawls out of the darkness into a sliver of light that illuminates his face. We hear the boy’s voice as he reminds himself to “keep cool,” but his mouth doesn’t move onscreen. Similar voiceover narration continues throughout the scene, communicating his thoughts to us without direct dialogue.

He tosses a glass bottle at a light switch, plunging the room into full darkness as he starts to play a game, as if he is hunting an enemy in battle. “Slowly… carefully… we have to get him alive,” his narration whispers over the darkness.

The camera movement and editing in the scene quickly becomes frenetic, and the sequence becomes surreal. New voices — a crying Russian woman, a shouting German soldier — rise alongside shrill noises on the soundtrack. We see fragments of the room illuminated only by Ivan’s flashlight: writing etched into the wall by long-dead prisoners of war, the corpse of a soldier, Ivan’s hand clutching the hilt of a knife, and the face of Ivan’s mother, who was murdered by German soldiers years ago.

The handheld camera spins chaotically through the shadows, picking up flashes of these images through the sparse available light, until it holds briefly on the frightened face of Ivan, whips toward the ground, then whips back up again to reveal Ivan’s mother staring directly into the lens. Voices moan on the soundtrack, and the camera tilts back up toward the bell…

The next shot prominently features the bell in the foreground, darkness in the background. The small figure of Ivan, seen from a high angle, is unnaturally framed on the bottom half of the screen only, two-thirds of the way across. He tolls the bell frantically as the camera dollies back into a wider shot of the room and a cacophony of moaning voices rise on the soundtrack.

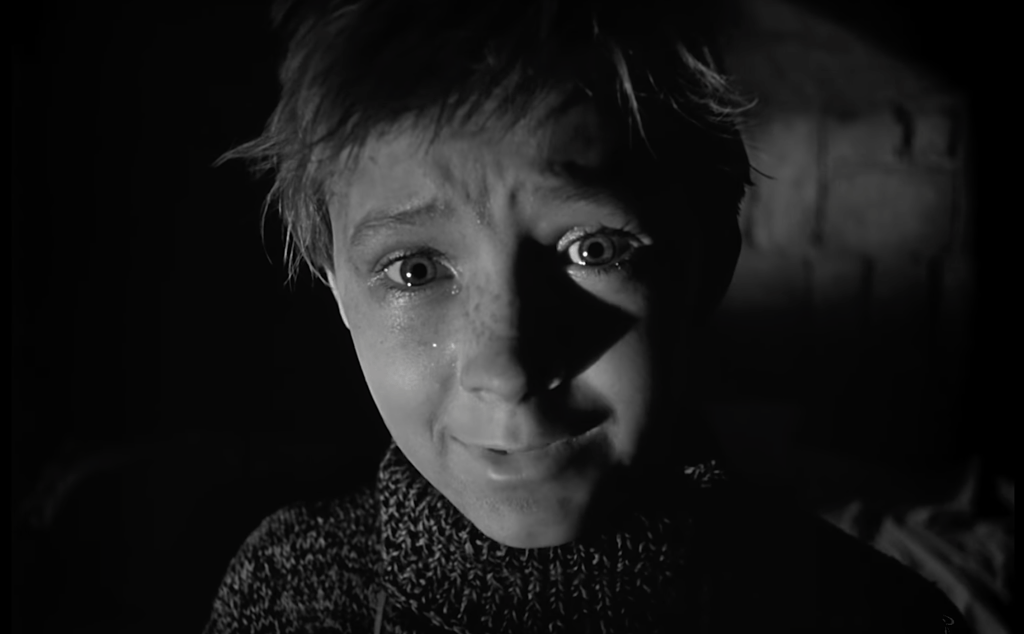

Ivan tries to gain control of his chaotic emotions by trying again to play his game. He searches in the darkness for his “enemy,” finally confronting the fabric of a soldier’s uniform with his flashlight. Tears well in Ivan’s eyes as he tells the uniform that he’s going to put it “on trial.” Tarkovsky holds on a close-up of Ivan. Tears drip from his eyes, an expression of fear passes across his face, and angry words spit out of his mouth — a full range of conflicting emotions, until he can’t take it any more and falls into darkness once more. Tarkovsky lets the camera roll on a shot of the boy on the ground as he cries in silhouette.

This scene is followed by a montage of explosions in various outdoor spaces on the Russian / German front.

The formal poetic license of this sequence — the way in which Tarkovsky experiments with chaotic camerawork, patches of near-total darkness, voiceover narration, and a blend of the imaginary and the real — elicits a visceral emotional reaction from us. It is as cinematic as scenes get: meaning is conjured through a clash of images, sounds, performance, shadow, and light.

And, the thematic meaning is communicated more elegantly in this abstract audiovisual sequence than it would be in a more traditional scene: Ivan is too old to be oblivious but too young to understand the horrors that he has been thrown into; he is a child, and so he can only make sense of the world through play, because he lacks the life experience to grasp what is going on around him. But what he is playing at elicits terrible memories and fears within him that he is not emotionally equipped to deal with.

Other scenes in Ivan’s Childhood are more firmly grounded in reality than not to set context — but this, along with several other abstract sequences, does not feel out of place because it is crafted in an organic manner, aligned with the main character’s point of view. It isn’t style for the sake of style, but aesthetics that place us in the mind of Ivan. In private moments, we bear witness to Ivan processing the horrors he has spent the majority of his life experiencing. Because he isn’t old enough to grasp the meaning — or lack thereof — of it all, it makes sense that the processing would be chaotic… which opens up a justifiable opportunity for Tarkovsky and his team to take poetic license in both storytelling and formal techniques.

Decisions to play with form in a way that reflects a character’s point of view elevates stylistic flourishes from merely being interesting to coming across as poetic.

The imagery in Ivan’s Childhood is evocative. In one scene, you feel like you’re living in the moment with these characters; in the next, it’s as though this is all a memory or a dream.

Flashbacks pull us out of the present and into the pre-war past of Ivan’s childhood in a variety of ways, contributing to this effect. Tarkovsky occasionally overtly cuts away to these flashbacks, as he does in the film’s finale, where we see Ivan running carefree on a beach at sunset with his sister. This overt cut to a happy flashback is done, it seems, to maximize the emotional impact of the film’s ending — as this edit comes directly after the devastating revelation and visual chaos of Ivan’s Childhood‘s tragic penultimate scene.

More often than not, however, Ivan’s Childhood evokes memory in subtler ways. One of those ways is through absence; in an early scene, we see Ivan watch a shellshocked old man try to hang a picture on one of the few remaining walls of his dilapidated, war-ravaged home. The old man acknowledges that his wife was murdered by Nazis, but cannot accept that his home has been taken from him, too; his efforts to decorate a place that no longer exists for a person no longer alive evokes the weight of war in a visually and dramatically compelling way. This is more interesting than seeing the events of the past would have been. Things absent in this old man’s space are called to our attention; through their absence, we conjure up our own memories of what might have been, and what war took away.

Tarkovsky also evokes memory in Ivan’s Childhood through sensory details to great effect. There is a beautiful transition early in Ivan’s journey in which Ivan, having slipped into a warm bath and a comfortable bed after a harrowing, dangerous mission, finally lets down his guard and allows himself to dream. Tarkovsky lingers on a shot of his hand dangling over the edge of his bed while bathwater drips from his fingertips. The camera then seamlessly tilts up to reveal that Ivan — in bed dreaming — sees himself inside of a well, in which he is also at the top, next to his mother, looking down into the depths below.

Fog. Explosions in sand. Moody, misty swamps filled with tall, skinny trees and murky water that separate the Russian and German fronts. Stoic, otherworldly birchwood forests that feel as if they are a world surreally removed from the violence taking place at its borders. Nature and all of its sensory details create transitions between sequences and allow us space to process the story — all that is real and all that is remembered by its characters.

Formal visual experimentation from a specific character’s point of view and evocative, sensory imagery elevates Ivan’s Childhood from what could have been a fairly standard war film into something much more interesting. But even in a film full of visual experimentation, Tarkovsky never loses the emotional core of the story that he’s telling, and is mature enough a filmmaker (even in this, his debut feature) to know when to simply hold on a close-up of a raw, charged performance.

Because of this, as much as I remember Ivan’s Childhood for its poetic imagery, I remember it for its faces, and the weight of the grief that they carry.