“You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful — to make this life a wonderful adventure.”

It’s hard to overstate how bold a movie The Great Dictator was for its time. Hitler’s army invaded Poland six days before Chaplin began principal photography, and the movie was written before the war broke out. The United States had not yet gotten directly involved in World War II when the film was released, and the full horrors of the Holocaust were not known even then. News of Hitler’s atrocities had spread through America, but the studio, United Artists, was wary of Chaplin making such an overt satire of the German leader and such a dramatic political statement, as they were afraid of international censorship. Chaplin was, in some ways, ahead of the times, if only by a few years.

The Great Dictator was also the first feature length “talkie” that Chaplin produced, and the first film in which his Tramp character (if you consider the Jewish Barber here to be the Tramp) coherently speaks. Political commentary was prevalent in several of Chaplin’s earlier films (Modern Times, The Kid), but to have his first talking picture directly address such serious matters was an inspired, risky, and groundbreaking choice.

Related to that, dialogue aside, it’s jarring to see the Tramp in war. Chaplin spent decades carefully crafting the iconic character, and the aesthetic preservation of the Tramp’s persona — even if the Jewish Barber isn’t directly named the Tramp — in The Great Dictator is a bold statement in and of itself. Seeing this innocent, bumbling character thrown into battle feels totally wrong… which is exactly why starting the film this way feels perfect.

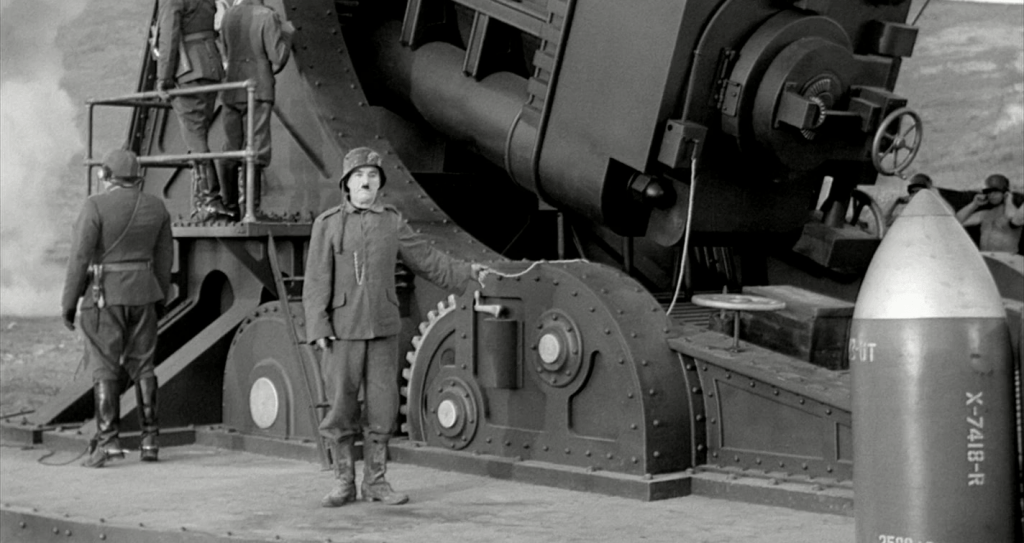

The movie opens in the trenches of World War I. Explosions erupts in the distance. The Tramp, decked out in military garb, pulls on a rope to launch a massive missile into enemy territory. It falls directly in front of the Tramp’s own battalion instead, and at first does not explode. Each person on the chain of command passes the responsibility to investigate the rogue missile down to their subordinate until there is no one left to take on the risk but the poor, innocent Tramp. As the Tramp investigates, sparks shoot out of the bomb and it starts spinning in circles. The Tramp runs away and the bomb explodes.

Later, the Tramp gets stationed at a machine gun, which he is tasked to fire directly at the enemy. The Tramp’s mannerisms and some of the dialogue throughout these scenes make the film seem more lighthearted than most war movies — but not enough to feel entirely comical.

Subverting expectations for what a Chaplin Tramp film should be right at the start of The Great Dictator is attention-grabbing, and these scenes set the tone for the rest of the film.

Many scenes in The Great Dictator toe the line between drama and comedy, like when Hannah whacks Storm Trooper soldiers in the head with a frying pan and accidentally hits the Jewish Barber, too, sending him tapping up and down the ghetto block in a loopy manner past storefronts labeled JEW. It’s funny to watch all of the men (including the Jewish Barber) agree that whoever finds a coin in their cake will be the one to blow up the dictator Hynkel, and then see them all discover, hide, and try to pass a coin off to their neighbors without getting caught, until the Barber ends up with them all jangling inside of his stomach. But the humor in these scenes carries a heavy weight, given the consequential reality of what Chaplin is satirizing.

There are many scenes that take place in the Jewish ghetto that aren’t humorous at all; Chaplin spends much time showing the Jewish men and women going about their lives under occupation. Some of the scenes — such as those in the barbershop, featuring the protagonist at work — are happy. Others are not. The Storm Troopers (Hynkel’s soldiers) rough people up, throw a noose around the Jewish Barber’s throat, and toss tomatoes at Hannah while laughing from the bed of a truck. Chaplin’s Dictator is a comedy, but it’s clear that he wanted it to first and foremost be a political statement; he does not shy away from showing occasional cruelty, even if he never portrays the full extent of the suffering that he condemns.

Chaplin’s greatest satirical accomplishment in The Great Dictator is, unsurprisingly, his comedic farce of Hitler himself, coded here as Adenoid Hynkel, dictator of the fictional country of Tomainia. There’s a brilliant scene in which Chaplin uses both a metaphor and physical comedy to speak to both the dictator’s delusional mindset and the impact that he’ll have on the world if left unchecked. In it, Hynkel asks to be left alone to reflect on the fact that he could become emperor of the world if his plans are successful; he maniacally laughs as he picks up a balloon globe, and smiles with more radiant joy than we’ll ever see his character have again as he bounces it up in the air inside of his palace over and over again.

Then, he squeezes it too hard and the world pops, leaving a melancholic Hynkel with nothing but a broken balloon.

In an earlier scene, Chaplin mocks Hynkel’s (and therefore Hitler’s) oratorial skills by dramatically spewing pseudo-German gibberish into microphones for a large crowd of spectators, occasionally sneaking words like “sauerkraut” into the mix for good comedic measure. His mannerisms and speech patterns at the mic are so ferocious that one of the microphones physically recoils during his speech, bending away from him in comic fashion until it sits at a 90-degree angle.

Chaplin gives a powerhouse performance as Hynkel — he is simultaneously comically childlike and unpredictably dangerous. The character that he makes the dictator out to be is appropriately unhinged. Hynkel exhibits no self-awareness — a particularly amusing conversation involves him calling for the extermination of brunettes (even though he is one): “A blonde world,” Hynkel decrees. “And a brunette dictator,” his Minister of Propaganda, Garbitsch (pronounced like ‘garbage’), retorts.

Chaplin spends a lot of scenes in The Great Dictator in private moments with Hynkel, in which the great dictator comes off as a dangerous, unpredictable, incompetent, petulant child who makes deranged decisions — like abruptly calling for the invasion of a competitor dictator’s country and then just as abruptly backtracking from that declaration, or casually ordering the slaughter of thousands of essential factory workers because they want to go on strike.

Chaplin’s Hynkel loses his temper at the smallest inconveniences, like a pen getting stuck to its holder, and whenever he has free time, he runs into a room where a painter and sculptor wait for him to stand as a model for a portrait and a bust. Much to the chagrin of the artists, Hynkel frustratingly leaves each time after only a few seconds. In another scene, Hynkel rewards his Minister of War with a new medal for his service, then a beat later rips all of the man’s decorative medals off of his chest in a bout of fury. These small moments are funny, but also economically and creatively expand our understanding of his character. And that character is not likable, however funny he may be. By the time Hynkel and his fellow dictator Napaloni (based on Italy’s Mussolini), physically fight with sausages and pasta over the details of a peace treaty, we don’t know whether to laugh at the character anymore or wish for him to meet a swift end. That is likely the point.

The most brilliant conceit in The Great Dictator is that the Jewish Barber and Dictator Hynkel look almost exactly alike — a fact on which the film’s dramatic, enthralling ending depends. It’s brilliant not just because it allows Chaplin’s Barber to believably sneak onstage at a Hynkel rally to make his fourth-wall-breaking, impassioned speech that pleads for peace and the renouncement of dictators. It also reminds us — much like the friendship between Storm Trooper Schultz and the Jewish Barber that developed in their previous life together as WWI soldiers fighting for Tomainia — that in spite of Hynkel’s (and Hitler’s) larger than life stature and oratorial skills, in spite of all of the power that he and his men seem to wield, the evil men are just men, possible to be mistaken for or replaced by any other, even ourselves. And that is perhaps the most powerful — and empowering — reminder of all that Chaplin has to say here.

Chaplin hopefully surmises at the end of The Great Dictator that “the misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed, the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people.” He reminds us passionately, however, that it is up to all of us to take action to ensure that this happens — and that when it does, we must collaborate with open hearts in order to create a kinder world.