“Perhaps you’re the woman I never met.”

The opening sequence of Three Colors: Red is a frenetic montage that begins with a close-up shot of the dial pad of a phone; the camera then tracks along the phone’s cable until it reaches the wall connector, where the shot dollies into the wall. Swirling images of red and white wires rolling in waves take over the screen. Then, the sequence cuts to a series of shots outside — the camera tracking into and out of the ocean, then underground below a city, continually following a path of cables while a cacophony of voices grows louder on the soundtrack. Then, abruptly, the scene settles on an extreme close-up of a flashing, orange, circular light. The voices disappear, replaced by the steady beat of a ‘busy’ dial tone. The lens racks out of focus; the flashing light becomes an abstraction.

It’s the perfect visual metaphor to open a film about missed connections and communication, throughout which characters spend so much time talking — without really communicating — on the phone. This montage is energetic, mirroring the feeling that comes to us with the potential of new human connection. But as the montage comes to a grinding halt, we’re left without a payoff — and a conversation is left unsaid.

Krzysztof Kieślowski constructed the narrative — and aesthetic approach — of Three Color: Red off of the theme of ‘fraternity,’ the value that the color red represents in the stripes of the French flag. The color red appears in nearly every shot of the film — sometimes subtly on a woman’s lips or a dog’s leash or in a faded rug on the floor, and other times, in bolder, vibrant ways that brilliantly dominate the color palette of a scene.

Color is not just treated as an aesthetic novelty, however. Red is such a bold, vibrant color that it easily draws attention to itself within the rest of the color palette of a given scene. Kieślowski uses this to his advantage, using color to orient us, draw connections, and steer our eye.

In her second scene, Valentine, the main character of the film, is photographed against a flowing red backdrop. The photographer snaps a beautiful, melancholic photo of her that is then plastered on a 65′ x 25′ poster above a busy Genevan intersection. The sheer scale — and bold, red background — of that image makes this profoundly sad portrait of Valentine impossible to miss. And yet, cars pass by it throughout the film, a passer-by walks in the crosswalk without giving it a single glance, and after several months, it is unceremoniously removed.

We get to know Valentine’s rich heart and depth of character throughout her journey in Three Colors: Red. She is vulnerable and kind; we empathize with her and grow to care about her. But to everyone else in Geneva, she is nothing but a face on a wall, devoid of personal connection, impossible to miss but easy to ignore.

In another scene, Valentine talks on the phone with her detached boyfriend, who is away visiting England. The alarm goes off on her street-parked car outside; we see the car blaring from her point of view out of the window as she ends her call. Then, the scene cuts to another character in another apartment, a man whom we’ve spent some time with but haven’t gotten to know in much detail. He hears the same alarm, which causes him to look out of his own window. We then see Valentine’s car, alarm blaring, from his point of view. His bright red vehicle is street parked in front of that window, and we watch as Valentine runs across the street in the background to silence her alarm. That frantic background action is a continuation of the previous part of the scene for us, but she is merely another barely noticed stranger to the man.

As Valentine turns off her car alarm in the background of the man’s point of view shot, a blonde woman walks around the street corner, sees the man’s red car, and notices him staring out of the window. She smiles and waves at him; he returns the gesture.

It’s an elegant storytelling moment. One action — a car alarm — triggers characters who do not know each other to cross paths in a scene without actually interacting, and seamlessly transitions the scene’s perspective from one character to the next.

This man’s red vehicle appears throughout the film, and every time it does, its distinct appearance lets us know that he is in the vicinity, even if we don’t clearly see him. We first see the vehicle in an early scene: Valentine leaves her apartment building and the camera pans to the right to follow her down the street; the camera then pauses as Valentine exits frame and the red car drives into the frame in the opposite direction. The camera then pans back to the left to follow the vehicle as he drives to his own apartment.

As we learn more about the man’s life, we catch glimpses of his vehicle around Geneva. Sometimes he is the film’s focus — other times, he exists in the periphery, in the same world as other featured characters who never get to know him. The color red guides our eye in the frame to the car, and allows us to unquestionably recognize his vehicle as it appears.

Visual motifs and other calculated aesthetic choices elegantly create connections for us throughout Three Colors: Red. Connections are also drawn through repetition of events in different characters’ storylines — particularly in those of the old judge and the aforementioned man with the red vehicle. There’s the abandonment of (and subsequent reconciliation with) dogs, and a dropped book in a crosswalk that in separate eras provides both men with information that later appears on a law exam. There’s romantic betrayal and subsequent loss. There are phone conversations during which things are left unsaid.

Repetition of events in the lives of different characters whose stories otherwise do not intersect makes a thematic statement that our lives and the lives of strangers may not be so different, even if the surface circumstances are not the same.

The fraternity explored in Three Colors: Red feels organic; this is not a film where multiple characters’ storylines converge and intersect in overly dramatic fashion. Instead, characters’ lives play out naturally, sometimes entirely on the periphery of others’ — but the actions and choices of one character’s life cause ripple effects that have impacts both big (like the loss of romance) and small (like a glance out of a window at a car sounding an alarm).

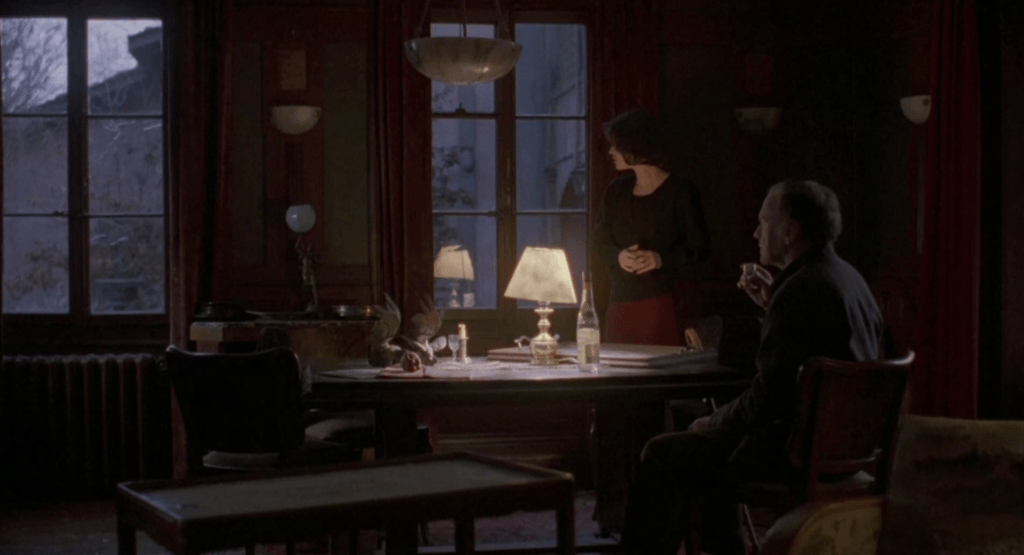

Coincidental events bring two unlikely characters, Valentine and Le Juge (an old, disgruntled, retired judge) together early on in Red; the rapport and relationship that develops between them forms the heart of the movie. At first, the old man appears to be irredeemable and cruel — the opposite of Valentine. He is melancholic, mysterious, and cynical; she is warm and loving. Both characters’ values are challenged and solidified through their interactions with one another.

At the beginning, you hate the man; after all of their interactions, you don’t necessarily like him, but it becomes much easier to see the world through his eyes.

When these characters part ways for the last time, a storm blows over Europe, and even more connections are made in the aftermath of a tragic event. The film’s ending at first feels forced, especially if you’ve seen the full Three Colors trilogy; after reflection, however, it feels like the perfect encapsulation of the message of Red: behind every stranger is a full life filled with emotion, depth, and pain that we can know if we have the patience, curiosity, and empathy to open our hearts to the people around us.