“I think I’ve lost my faith.”

Halfway through Regan’s exorcism, the two exhausted priests, Fathers Merrin and Karras, sit on the stairwell outside of the possessed girl’s bedroom. Director William Friedkin positions them facing in opposite directions on the stairwell, with the railing between them; framed in close-ups, they almost appear to be in a confessional booth. The tenor of their dialogue, along with the weighty presence of actor Max Von Sydow as Merrin, makes you feel — if just for a moment — like you’re watching a scene out of an Ingmar Bergman film.

“Why this girl? It makes no sense,” Karras asks, exasperated.

“I think the point is to make us despair,” Merrin replies. “To see ourselves as animal and ugly. To reject the possibility that God could love us.”

The Exorcist is legendary for its scenes of gruesome, supernatural terror — like that of Regan crawling backwards, crab-like, down the stairwell of her home with her head spun completely around and her mouth spewing blood. It is also infamous for its shocking content, like the vile and horrible things that Regan says and does while under the devil’s possession, and the horrifying way in which her face and body deteriorate while under his evil grasp.

But it’s those existential asides, and the depth and breadth of character development in between them, that makes the terror linger with us long after the credits roll. Shock and horror punctuate the narrative, but they do not drive it forward. There is a deep sadness — an existential anguish — that affects nearly every character in this film. Regan’s possession, which would be the sole focus of the story in a lesser movie, is merely the central hub that connects all of the spokes of their turmoil and dread.

What happens to Regan is absolutely terrifying, to be fair, but the lingering unease caused by The Exorcist doesn’t come from the abrupt flashes of demonic faces cut into the edit, or from the possessed Regan vomiting pea-green liquid gleefully on to a priest.

That supernatural shock grows out of horrors that are distinctly of this world. The audience can’t stay detached from the terror because it is framed by things that we can relate to on a human level.

The least compelling moments of The Exorcist are the infamous ones; we can remove ourselves from the story of a character being possessed, no matter how disturbing that content might be.

But the terror of Regan’s story isn’t just that she is possessed by the devil, but that she is subjected to medical test after test and no doctor can so much as diagnose her, even as her situation becomes more and more dire. The terror that her mother, Chris MacNeil, experiences is not just that the devil is in her home, but that her daughter is deteriorating before her eyes, yet she is completely helpless to save her.

One of the most difficult scenes to watch in the entire movie takes place before Regan even fully falls under constant possession; in it, she lies in a hospital bed in a “normal” state, and is subjected to a battery of medical tests. A catheter is inserted into her neck, blood squirts out, and then a cacophonous machine slides down over her head to X-Ray her skull. She screams. After a few viscerally disturbing inserts of the blood squirting, the procedure is largely framed from Regan’s mother’s point of view; the reverse shot from Regan’s point of view shows the deep panic and pain in her eyes. The glass barrier between Chris (the mother) and Regan (the daughter) adds to the sense of helplessness that she so clearly, visibly feels. Chris can’t reach out to comfort her.

Later, Chris meets with more than a dozen doctors in a hospital conference room. Nobody has any answers for her. Chris yells at them about how she’s been through “eighty-eight doctors” and no one can help her. Friedkin frames this moment in a wide shot from overhead, making the people all feel small and helpless. He then lingers on shots of the doctors at eye level, portraying them neutrally — neither inept nor helpful, just human and lost.

The Clinic Director in this scene insinuates that Regan should seek out an exorcism. Chris looks at him in absolute disbelief, and Friedkin lingers on that reaction in a tighter frame. “You’re telling me that I should take my daughter to a witch doctor? Is that it?”

That’s it. That’s all that the medical community has to offer her.

This back-and-forth between Chris and the Clinic Director harkens back to an earlier conversation in the film, during which another doctor decided that Regan was “hyperkinetic” — presumably a diagnosis of ADHD — and prescribed Ritalin for her. When Chris asks what the Ritalin will do, the doctor responds with, “Nobody knows the cause of her hyperkinetic behavior in a child. The Ritalin seems to work to relieve the condition, but we really don’t know how or why, frankly.”

“We really don’t know how or why.”

By spending a considerable amount of the movie’s runtime on these kinds of scenes, Friedkin presents us with supernatural terror in a way that we can deeply, disturbingly relate to: the horror of being helpless to save someone (in this case, a child) from a medical condition (in this case, one beyond doctors’ comprehension).

It also elicits, for us and for the characters, the horror of realizing that the people who you thought would have the answers, don’t. And in situations where you are desperate for help, that can leave you feel hopelessly lost.

The inability for medical professionals and even spiritual leaders to provide clear guidance creates, for the characters that they interact with, a crisis of faith — both secular and religious. The secular crisis is explored in the multitude of aforementioned medical scenes. The religious crisis is most deeply explored in Father Karras’ subplot, which comes to a head in the end with the separate religious crisis of Regan’s possession.

The horror of Father Karras’ story is not only that he must confront the devil, but that he is forced to confront his own shortcomings and face the torment of wanting to help people, but finding himself unable to live up to that calling.

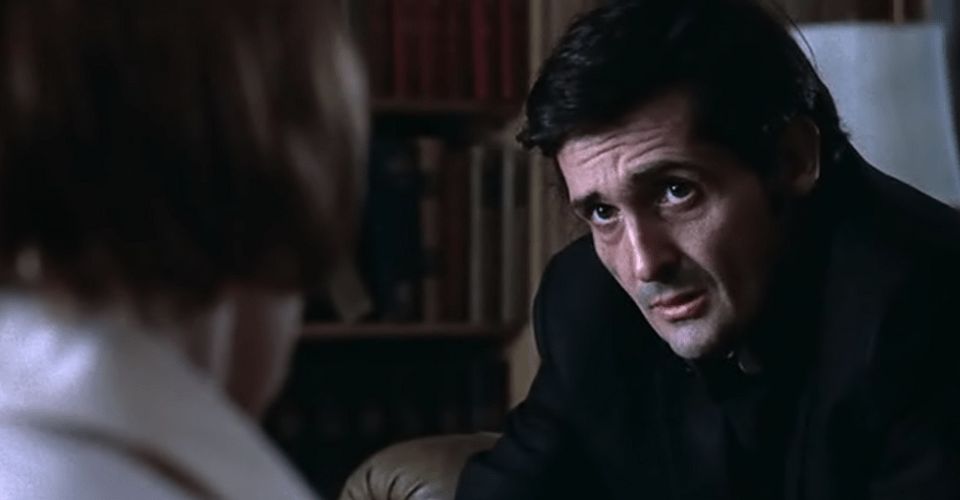

“I need out; I’m unfit. I think I’ve lost my faith, Tom,” he tells a fellow priest sitting across from him in a dark wooden booth in a smoke-filled bar. The scene ends there, without resolution; Karras, against his better judgment, carries on doing what he is doing.

What else is he going to do?

There’s a deep sadness to his eyes every time we see him, even when he smiles. When a friend visits Karras in his tiny, untidy apartment, Friedkin lingers on a nearly empty bottle of scotch on the floor in the room’s defacto establishing shot. His character is prominently developed via a subplot involving his mother, the outcome of which then is mirrored in his failures during Regan’s exorcism, which makes his sacrifice at the end all the more meaningful, compelling, and tragic.

Father Karras’ first major action in the movie is to travel all the way from DC to New York to take care of his ailing mother. It’s a noble act, and we think highly of him for it. But before he gets to his mother’s apartment, he does something that contrasts sharply against that nobility. As he steps on to the NYC subway platform, we see a homeless man seated on the floor; the man asks, “Father, can you help an old altar boy? I’m a Catholic.”

The subway train races into the station, and as it does, we see the homeless man’s face light up in a harsh close-up, then plunge into darkness, then light up again in rapid succession as the train cars pass by. The reverse close-up of Father Karras shows him as a disinterested, disgusted, disgruntled middle-aged man who walks away from a man in need.

The dichotomy conveyed in this introduction defines his character, and his character’s arc introduces existential themes into the story that both add thought-provoking depth on their own — some of Karras’ scenes might not be too foreign in an Ingmar Bergman, crisis-of-faith movie — and support the main story by both opening space up for us to think about religious themes while we experience a tale of demonic possession.

His storyline complements, then mirrors, then collides with the primary storyline in a compelling way. That he ultimately overcomes the greatest evil in spite of his doubt adds great dramatic weight to the story.

All of the primary character introductions give us important context about the characters. Regan is introduced to us as a sweet and innocent young girl, who kisses her mom happily and talks earnestly about how much she loves horses. The contrast between these scenes of her at the beginning and her subsequent demonic personalities makes her descent after possession all the more scary.

Chris is introduced as a single, working mother — it’s clear that while she’s devoted to her work, she is far more devoted to her family. The manner in which she reacts when Regan causes an embarrassing disturbance at a party is indicative of this, and the way in which she avoids asking some characters for help, but then asks it from others, is an excellent case study for how to write a strong, subtly nuanced character through dialogue.

Because all of the primary characters are so strongly developed, we feel the terror of what happens to them much more strongly than we would if they were superficial or underdeveloped.

The Exorcist is also terrifying because it relies heavily on a mix of shock and offscreen terror — not just one or the other. It veers into excess onscreen at key moments to unnerve us, and at other times, it shows restraint. The two main deaths in the film, for example, happen offscreen. The insinuation of what Regan did in the first instance, and then her possessed smile and calm demeanor after the second, are far scarier than seeing the murders onscreen ever could have been. In a movie full of shock, it’s the scenes of restraint that are, perhaps, the scariest.

The Exorcist is lauded as, perhaps, the best supernatural horror film of all time — but it is a great movie not for its supernatural elements, but because it understands true horror on a human level, and makes us painfully, viscerally confront it.

It supports its tale of supernatural horror with real-life horror in order to generate empathy in the audience.

Then it shocks us.

Then it introduces character subplots that make us think, and have those subplots intelligently collide with the primary story in a way that never feels forced.

A lot of that can be attributed, surely, to the quality of writing of William Peter Blatty, who penned not only the screenplay but the book that the movie was based on. But credit is due to everyone involved; The Exorcist is also successfully horrifying because of the dark and brooding atmosphere, and the assured framing and blocking, by Friedkin and his crew. And, the terror is felt because of the exceptional performances from the phenomenal cast, which convey all of the despair and helplessness and strength and fear that their characters carry with dynamic believability.

By the time we get to the exorcism itself, we’re already exhausted. Then, tragedy continues to relentlessly unfold.

In the final scene, The Exorcist becomes bittersweet; Regan’s final moment with Karras’ priest friend is a touching send-off for both characters, and wraps up the story on a touching note. There is hope for a brighter day in spite of all that they’ve been through and all that they’ve lost.

But the subtle scars on Regan’s face in the end indicate that all that’s happened has indisputably left a mark.

And after all of the preceding events, and in spite of the optimism of that final scene, we leave reminded of some of those painful, human truths…

… and thus, the horror lingers, not because of the supernatural, but because through excellence of craft, Friedkin and his team used the supernatural as inspiration to bring the horror a little too emotionally close to home.