“I may already be dead, just not typed.”

“Some plots are moved forward by external events and crises,” Professor Jules Hilbert tells Harold Crick, as Crick, in crisis, tries to figure out how to get the woman in his head who is narrating his every move to stop. “Others are moved forward by the characters themselves. If I go through that door, the plot continues: the story of me through the door. If I stay here, the plot can’t move forward. The story ends.”

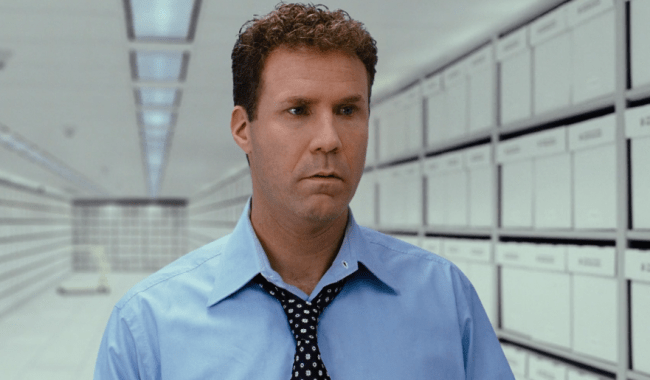

Harold Crick, fearing his imminent demise should he make any choices at all, sits on the couch in his sparsely-decorated, unexceptional apartment all day long the next day, watching TV, not even moving to go to the bathroom. He watches nature documentaries, and when the violence of nature hits a little too close to home, his impulse is to change the channel… but he stops himself, his hand lingering over his remote control… if he doesn’t make any choices, those choices won’t have ripple effects…

A construction crane suddenly crashes through the drywall, smashes the furniture in his living room, and lifts debris out into the courtyard below. Crick clings against the back wall of the room for dear life, screaming over the hideous sounds of crunching metal.

As a piece of metafiction, these back-to-back scenes are the most concrete — pardon the construction pun — example of what Stranger Than Fiction is about. Certainly, Harold’s story is about another thing entirely: taking charge of your life and living it the way that you want to in every moment, because the longevity of your life is not at all guaranteed.

But that story is only half of the narrative here. The other half — which gives his story structure — is about writing itself. It stands to reason, then, that the themes of that story are about literary convention and dramatic writing.

The primary lesson of that half of Stranger Than Fiction, exemplified by the comedic ridiculousness that ends the aforementioned sequence, is that stories should be steered by their characters according to what the characters want and who they are… not by the author imposing situations upon them in the service of contrived drama or plot. If the author’s desire to create drama or force a plot point out of a situation is resolved by introducing external forces and not through organic character choices, you get the dreaded deus ex machina — the crane crashing through the wall. It can be surprising, but it’s not dramatically satisfying.

The narrator of Stranger Than Fiction — author Kay Eiffel — aborbs this lesson directly by meeting her latest protagonist face-to-face, in the flesh. She had became famous for killing off her protagonist in every single novel that she had written. She then spent ten years trying to figure out how to kill Harold Crick in her latest book, presumably for the sake of drama… because she felt that that is what she had to do and what audiences would want to read.

Her decision at the end of the movie isn’t just an empathetic resolution that gives Harold Crick the jolt that he needs to take charge of his life and live it to the fullest — though it is that, too. It’s the realization that she is trying to force drama for the sake of theme and plot, as opposed to what her characters want or deserve.

“I realized I just couldn’t do it,” she tells Professor Hillbert. “Because he’s real?” No: “Because it’s a book about a man who doesn’t know he’s about to die and then dies. But if the man does know he’s going to die and dies anyway, dies willingly, knowing he could stop it, then… I mean, isn’t that the type of man you want to keep alive?”

Characters drive plot. Not the other way around.

Harold Crick’s story is less self-referential, but, being that it is literature-come-to-life, it is still full of symbolism.

Crick’s watch is the most obvious of the recurring symbols. That the watch literally saves his life in the end is a clever reminder that it is the persistent march of time that — when heeded — saves us from a life unfulfilled by reminding us that our time is limited and should therefore be used to the fullest.

Crick’s obsession with counting inane details in his day-to-day life like toothbrush strokes and the number of floor tiles in any given room is a pervasive character quirk in the beginning of the film, but goes away in the end. This shift serves as a visual and thematic expression of his personal growth. As he obsessively counts things at the start of the movie, graphic overlays visualize the numbers and spatial relationships between those things. The graphics are fun, but distracting. When that all goes away, Crick can better focus on what’s right in front of him, and without the graphics, we can, too.

It’s a twofold reminder that if we are to live our best lives, we can’t miss the forest for the trees… and it’s best to devote your full attention to the important things — and people — in front of you instead of staying trapped in your own head.

The environments that Harold lives, works, and socializes in have all been carefully designed to visualize these themes. Harold’s apartment is bland and boring; he has the most basic, uninteresting furniture and there are no decorations on the walls. He works as an auditor for the IRS; at work, we mostly see him in one of two spaces, each of which are extraordinarily uninspiring: a row of cubicles, and a deep hallway filled from the floor to the ceiling with white boxes of tax files.

Harold finds himself in significantly more interesting places after he decides to live his life more boldly.

Ana’s apartment is full of color and personality; it is warm and cozy and a little bit chaotic, like her. His friend Dave’s apartment feels futuristic, and the bed has a comforter with rockets and stars printed on it; the home reflects Dave’s personality — an adult whose biggest unfulfilled dream is to attend NASA Space Camp — and is a reminder for Harold of the importance of holding on to childlike wonder as an adult.

And then, there’s the guitar shop, with its red walls and colorful instruments, where he seeks out a Fender Stratocaster in the first major step down a new path of commitment to spending his time truly living instead of just existing.

Every detail, big and small, in the movie’s design contributes to our understanding that Harold’s life is much more fulfilling when he makes active decisions to do what he wants to do.

That, coupled with the literary analysis that we can pull from Kay Eiffel’s part of the storytelling, is a poignant reminder that our stories are much better when we don’t let external circumstances swoop in to change our fate… but choose our own fate through the actions we take.