“Quit stalling! Get back to work!”

In all of his most famous films, Charlie Chaplin framed his stories from the perspectives of poor and working class people in order to generate empathy for those less fortunate in society. His impoverished Little Tramp made us laugh, but also pulled on our heartstrings as he took care of an abandoned child (The Kid) or was rejected by his romantic interests and supposed friends because of his social standing (City Lights). Poverty was often a theme in Chaplin’s work. But it wasn’t until Modern Times that he made a feature-length movie that entirely, overtly examined — and comedically condemned — some of poverty’s societal root causes.

The story of Modern Times focuses on how the ruling class exploits the back-breaking labor of blue collar workers to gain wealth for themselves while the laborers struggle to put food on the table or a roof over their heads with the wages they are paid. It was a relatable story for people alive and struggling when Chaplin made the film near the end of the Great Depression… and it is, sadly, just as relevant today as the gap between rich and poor widens to historic levels and the cost of living soars.

Chaplin, as the Tramp, plays a factory worker; he and his fellow laborers are treated as nothing more than cogs in a wheel. They are expected to maintain machine-like efficiency and are never to rest on the job. In one of the film’s most famous scenes, the Tramp jumps into a machine in order to keep up with the ever-increasing pace of the assembly line and rides on the turning gears inside, literally one with the machine… until it spits him out.

The visual metaphors aren’t subtle, and they aren’t meant to be. Chaplin goes big here, both for laughs and to make his message loud and clear.

The movie opens with a sequence that pays homage to the opening scene of Fritz Lang’s classic silent film, Metropolis, which is also about social inequality and labor exploitation. In the opening scene of Lang’s movie, men somberly march in orderly, single-file lines through a tunnel during a “shift change” at work. Chaplin opens Modern Times with a shot filled from side-to-side, top-to-bottom with sheep being herded in a single direction. He then crossfades to a shot of a crowd of men in coats and jackets filing out of a subway exit, all moving in the same direction… being herded much the same.

We follow some of those men to a factory run by the Electro Steel Corporation. There, the Tramp works on an assembly line, where his entire job consists of twisting hex nuts on steel plates with a wrench at ever-increasing speeds. Any time he walks away from the assembly line, his body twitches to instinctively continue that perpetual, monotonous motion; the work gives him such a one-track mind that any time he sees a hex nut-shaped object — even if it’s a button on a woman’s blouse — he goes after it with his wrenches, desperately needing to turn it. Late in the movie, the Tramp returns to the factory to assist a mechanic with his day-to-day work; so used to a job where he only has to do one move over and over and over again, the Tramp stumbles through the ever-changing tasks, and ends up dropping tools underneath a crusher and into the gears of a massive machine. Then, when his boss gets stuck inside of the gears of that same machine, the Tramp attempts to rescue him… but when the lunch bell rings, he instinctively walks away to eat his food. The factory has classically conditioned him to be a machine himself: don’t think. Just do.

The President of Electro Steel Corporation, meanwhile, is seen at the start of the film sitting at his desk in a spacious, comfortable office leisurely building a puzzle while his workers race around on the factory floor below, adhering to his orders to continually “speed it up.” The Tramp tries to take a smoke break in the bathroom, but barely gets to light up before the company President’s face appears on a massive monitor behind him to say, “Hey! Quit stalling! Get back to work!” The difference between his work day and his workers’ days is made as stark as possible, for the message to be as clear as possible.

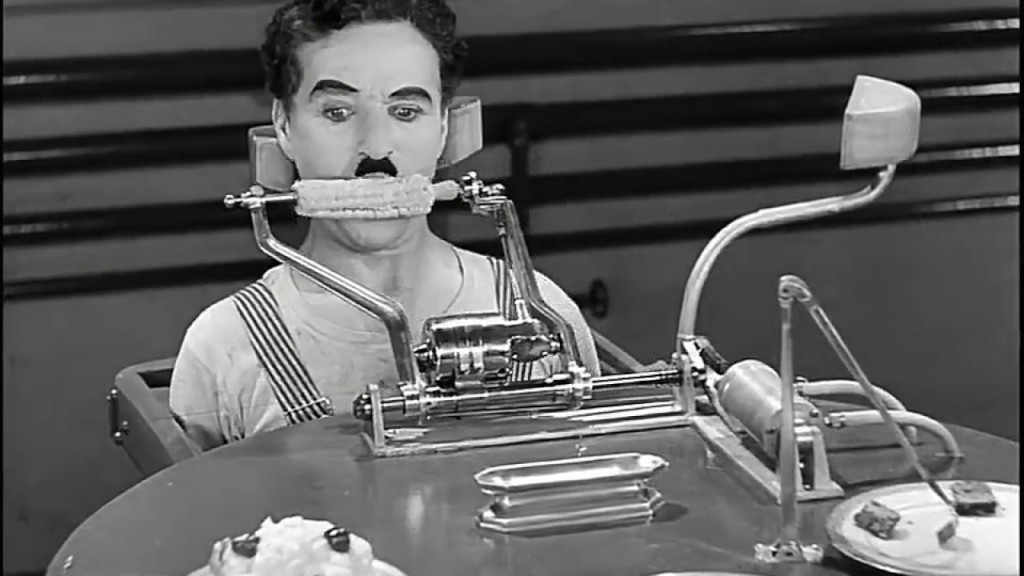

The funniest scene in the movie sees the Tramp as a test subject for the Billows Feeding Machine, a monstrosity designed to “eliminate the lunch hour” so that the factory can substantially increase productivity. Chaplin stands there in horror, clamped into the machine, while it spills soup on his shirt, whirls corn at absurdly high speeds against his mouth, whacks him repeatedly with a cloth, and, of course, pies him in the face. It’s hilarious physical comedy turned satire by the factory President’s reaction to it: he never asks if the Tramp is okay; he simply refuses to buy the machine because “it isn’t practical.”

The Tramp’s Factory Worker has a nervous breakdown from all of the stress that he is under at work; when he emerges from the hospital, Chaplin cuts to a montage of canted angles of cars and crowds bustling through busy city intersections to represent not only the Tramp’s internal chaos, but the mad pace of the industrialized world at large. In the factory scenes between the opening shot of herding sheep and this montage of chaotic urban imagery, Chaplin makes a statement on the inhumanity of capitalist, industrial society.

But that’s only act one.

The factory scenes are so visually rich (and so funny) that it’s a little disappointing to leave them behind as the plot moves on, but leave them behind Chaplin must in order to explore his ideas more deeply.

The Tramp ends up in jail shortly after his release from the hospital for (accidentally) participating in a communist rally, which is promptly shut down by the police.

In jail, the Tramp becomes a hero; he stops an armed jailbreak attempt and is allowed to converse casually with the guards and decorate his cell. He feels so comfortable there that he even hangs a “Home Sweet Home” sign above his bed. The prison system doesn’t force-feed him by machine in order to remove the need for a lunch break; instead, he is able to have a sit-down meal with his fellow prisoners (though one that admittedly ends poorly when “nose powder” is mistaken for sugar). Yeah, they’re behind bars and are forced to march in a single-file line to the dining hall whenever it’s time for a meal. But compared to the factory, it doesn’t look too bad. When the Tramp is granted permission to leave and return to the world — and the workforce — he earnestly asks, “Can’t I stay a little longer? I’m so happy here.” That about says it all.

Using the prison setting as a foil against the factory setting may sound extreme on paper… but it makes Chaplin’s point crystal clear, while also allowing room for great comedic scenarios amidst the social statements.

Chaplin used “B stories” following other characters in several of his other movies to explore a theme more deeply than could be explored with just the Tramp. Modern Times is no different. As Chaplin’s Tramp drifts from job to job after his stint in jail, Paulette Goddard’s character “The Gamin” resorts to petty theft in order to put food on the table. Her family’s desperation — and later, their tragedy — drives her to lose hope over time.

Fate then has her run into the Tramp. Of course, they are smitten with one another — what would a Charlie Chaplin silent film be without the Tramp falling in love at first sight? But the merging of these two characters’ storylines isn’t just for the sake of romance; it is a poignant and thematically meaningful storytelling device.

Together, they sit outside of a middle-class home and Chaplin creatively fantasizes about what their life could be like together as man and wife in a proper home. Chaplin becomes a night watchman in a mall in order to generate an income for them — in the mall, they fantasize about what life could be like together if they had money to buy the things he is in charge of guarding, too; she sleeps in a bed in the furniture department and he roller skates around without a care in the world.

Chaplin ties his plot threads together further by bringing in one of the Tramp’s former factory coworkers as a petty thief in this mall sequence. At the end of a robbery attempt gone wrong, the police show up — as they have over and over and over again throughout the film. The repetition of this — the police always showing up to crack down on the main characters’ activities — sends a clear thematic message: capitalism keeps working-class people in poverty, and the police enforce the criminalization of poverty by cracking down on crimes caused by the desperation of the poor, in order to help keep them poor.

The Tramp and the Gamin band together and support each other — she even gets the Tramp a job that he is wildly unqualified for, to amusing (and musical) results. But in the end, the only home they can afford to live in is an abandoned shack with loose ceiling rafters, and they are ultimately forced to leave the town that they know because it is clear that they are not wanted (at least, not as impoverished as they currently are).

Chaplin’s greatest silent films — of which this is one — make us laugh… but they also have something meaningful to say. Modern Times weaves two stories together — one of a factory worker who tries his best to do well, only to end up in and out of jail; and one of a poor woman who steals to survive and who then is also threatened with jail. In doing so, Chaplin’s comedy becomes a social statement.

It’s a special kind of movie — you laugh at a man getting whacked in the face with an ear of corn, then feel enraged at societal inequality and exploitation. That alone warrants praise and study; the comedy and the commentary exist in harmony — the way our society operates is absurd and so the story can be, at times, hilarious, but it also hits a little too close to home. And because of that, even after all of the comedy, as the Tramp and his partner walk down the street, we aren’t left laughing, but reflecting.

One thought on “Modern Times (1936)”