“The train was late and I missed the bus. Were you worried?”

The bus stop is nothing more than a sign posted on a concrete slab on a muddy road in the middle of the woods. Satsuki and her younger sister, Mei, wait there for their father in the a torrential downpour. It’s a dreary scene — the rain falls down hard all around them, the forest is dark, and the people who get off of the bus when it finally arrives keep their heads angled toward the ground. Their father is not among them.

“Daddy wasn’t on it,” Mei says, with a frightened expression on her face. Satsuki, too, looks concerned.

Mei wears a puffy blue raincoat and salmon-colored galoshes; her sister wears light blue galoshes, an orange skirt, and a yellow blouse and holds a bright red umbrella. They are singular points of vibrancy within an otherwise muted color scheme.

Mei splashes around in puddles and tries to climb a tree as they continue to wait for their father. The rain falls harder and the road gets darker. A lamp illuminates above them, shining a bright yellow light on the bus stop. Satsuki lets Mei hop up on her back so that the tired young girl can take a nap. Then, Satsuki spots big, grey paws walking toward her. Before she knows it, Totoro stands beside her, wearing a big leaf on his round head.

Her eyes widen — first in surprise, then with delight — as she shares an umbrella with her large, fluffy friend. The vibrations of the rain on the umbrella make Totoro giddy; he yells and bounces. Suddenly, two lights appear in the distance and before they know it, a Cat Bus is in front of them. Totoro hitches a ride on it and takes off into the distance… just as the father arrives on the next regular bus that pulls up to the station.

The father apologizes for being late, then looks momentarily horrified as his children tell him that they “met Totoro” while they were waiting for him. But when they start running in circles around him and laughing, he smiles. He’s thrilled that his kids are having a good time, and that they’re safe.

This one scene encapsulates nearly everything that Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro is about, and all that makes it compelling. Though not as complex, extravagant, or nuanced as, say, Spirited Away or Princess Mononoke, Totoro is much-beloved as a parable about the power of childhood imagination to make sense of difficult situations, build resilience, and find light and joy in the darkness.

Mei, Satsuki, and their father move to a new home in the countryside at the start of the film to be closer to the hospital where their mother, afflicted with a serious illness, is staying for treatment. Their father spends his days — and sometimes nights — working to provide for his wife and kids; an elderly nanny takes care of the children during the day. The children run and play, and try their best to stay positive and happy in their new environment.

The adults shield them from the seriousness of the situation as much as possible — which is why we, the audience, never learn much about their mother’s medical situation. In many of the scenes in which we see the mother, we view her from afar; it’s something that is happening on the periphery of the story, but since the movie is told from the point of view of the children, we know about as much as they know.

The adults prefer it that way. It’s indicated in the end that the mother is, in fact, going to overcome her illness and get better, but it’s still a serious situation, and Mei and Satsuki’s father doesn’t want them to dwell on it or worry too much about something that they cannot control. So, he happily lets them escape into their own fantasies.

When the kids move into their countryside house, they immediately start to see things that the adults cannot see — round, black balls with eyes scatter about in the attic and roll up and down the stairs. The children chase them around, and when they return downstairs to their father and nanny, the nanny notices soot all over their hands and feet.

“That must be the soot spreaders,” she says. “They breed in empty old house and cover them with soot and dust. I could see them when I was little. Now you can too, huh?” She smiles, and the children are pleasantly shocked that she could see the “soot spreaders” once upon a time, too.

Mei and Satsuki see more imaginative creatures the more time they spend playing in the fields and forests around this home. Totoro — and his little totoro friends — are the most joyous; Cat Bus the most mysterious. The adults just see kids running around and laughing; but through the children’s eyes, we see them interacting with fantastical, friendly beasts.

In one scene, Totoro, his friends, and the children wave their arms in a garden in the evening; their father, working in the nearby cottage, merely sees his kids playing together. In Mei and Satsuki’s eyes, however, a massive tree sprouts from the ground and grows to be the tallest tree in all the land. Totoro conjures up a spinning top, and carries them on it up, up, up into the sky so that they can sit on top of the tree branches and take in beautiful views. The musical score in this scene is aspirational, emotional, and full of wonder.

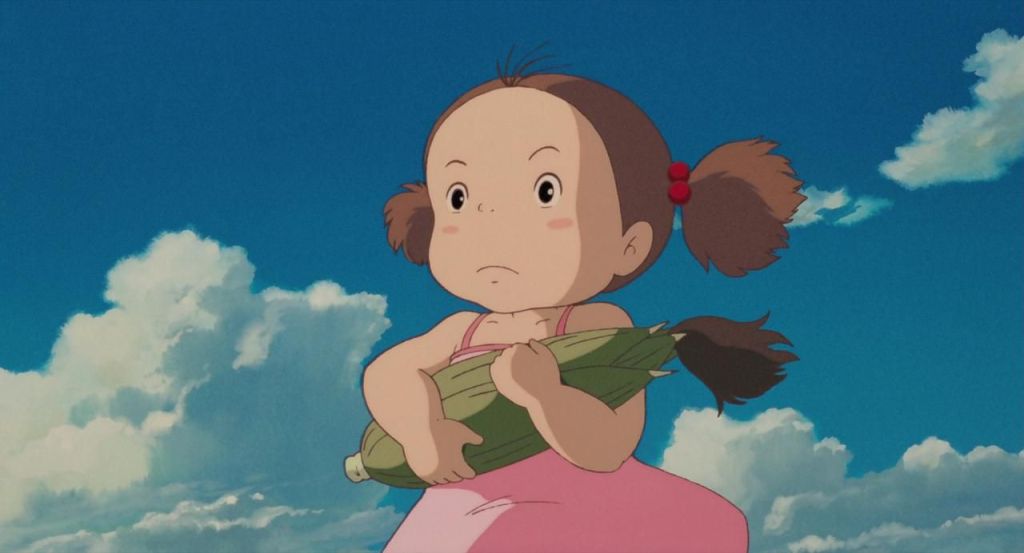

The adults encourage such imaginative thinking. The nanny picks vegetables in her garden with Mei and Satsuki near the end of the film. She tells the kids that the vegetables in her garden are special — that they’re good for the body and the soul. “They wouldn’t help my mother, would they?” Satsuki asks. Nanny doesn’t hesitate with her response: “Of course they would. My vegetable garden is bound to make anyone feel better in no time at all.” Mei takes that statement to heart; thinking that an ear of corn can heal her mother, she clings on to it with fierce protectiveness.

But the adults can’t shield the children from all of the darkness of adult life. While their father works, Satsuki receives a telegram — meant for their father — notifying the family that their mother has fallen ill. We later learn that it was nothing more than a cold, but without much-needed context and without their father being around for reassurance, the children begin to panic and break down in tears. Mei, clutching her ear of corn close to her chest, runs away, desperate to make it to the hospital to give her mother the life-saving vegetable. She protects it from a ferocious, hungry goat — “No, this corn is for my mommy!” — and her recklessness causes the whole town, and Satsuki, to start a search party to bring Mei back home.

Satsuki, scared for her sister’s life, begs for help from the only one who has been able to help her make sense of it all: Totoro. She falls on to his big, fluffy belly, waking him up from a nap, to ask for assistance: “Please help me find her — I don’t know what to do.” Totoro hugs her and smiles, and they soar above the trees to summon the Cat Bus, who escorts her over power lines and through fields and forests to Mei’s side, and then on to the hospital. While she’s on the Cat Bus, the music is energetic, jazzy, and hopeful — she feels like she can overcome any obstacle.

When Satsuki and Mei arrive at the hospital, they peer through the window and see their mother and father happily conversing. They smile, knowing that she is safe. They laugh together, sitting on a tree branch with the Cat Bus hovering behind them. They leave the ear of corn on her windowsill; because they’re children, it’s all that they know how to give. It’s a whimsical enough gift to make their mother smile, and thoughtful enough to communicate their love.

Their play is distraction; their imagination is comfort.