“I thought we wouldn’t be like them.”

They sit across from one another in a red booth in a diner, talking about accessories. He asks her where she got her handbag; he thinks that his wife would like one of the same. She tells him that her husband bought it for her on a business trip out of the country; it is not for sale in Hong Kong. She asks where he got his tie, thinking that it would look good on her husband; he replies that his wife bought it for him out of the country, and that it is also not for sale in Hong Kong.

“Actually,” she says, revealing her bluff. “My husband has one just like it. He said it was a gift from his boss.” “And my wife has a bag just like yours,” he replies. “I know – I’ve seen it,” she says.

“I thought I was the only one who knew,” she says. “I wonder how it began.”

With this dance of carefully calculated dialogue, neighbors Su and Chow reveal that they know that their spouses are having an affair with one another.

We never see that affair. We don’t even see the spouses’ faces. They are as absent in the movie as they are in their marriages. When Su asks her husband to buy her the aforementioned handbag earlier in the film, we linger on a medium shot of her in the hallway throughout the entire exchange. It feels odd to never see the husband as he speaks, but it is the perfect visual representation of their detachment.

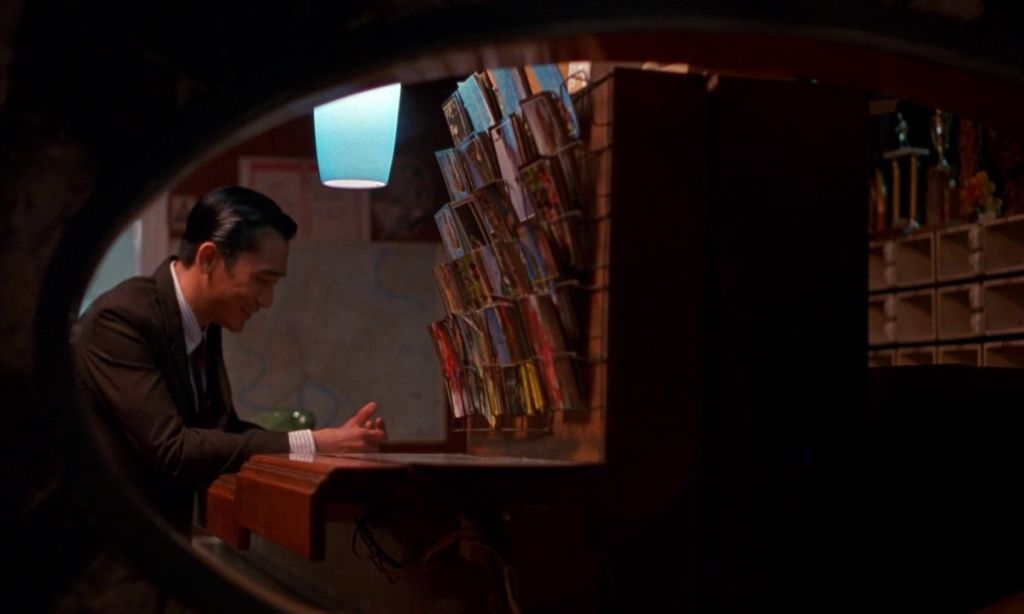

A similar visual detachment occurs as Chow finds out about his wife’s affair. One evening, she calls him from her office to tell him that she has to stay at work late. We only see the back of her head and the phone as she speaks. Chow shows up to her office anyway to take her out to dinner. “Didn’t she tell you she was off early today?” her boss asks him. “She never remembers to tell me,” he replies. We never see the boss during this exchange…. just Chow, alone at the edge of this obscured frame:

In this movie about hidden romance, the characters are often hiding within the frame.

And as Su and Chow begin to spend more time together, more shots in the film become increasingly obscured. When Chow calls Su at work, the camera lingers on the clock above her boss’ office instead of on the conversing characters. We see fragmented shots of them in mirrors, or framed-within-the-frame through windows or doors or bars, or from afar around the corners of buildings across the street.

In my favorite scene, they talk and eat ramen together in his apartment. Their landlord returns to the building unexpectedly with friends to play mahjong. Su cannot return home without arousing suspicion. Afraid of starting rumors, they stay together in the apartment until the coast is clear. As they decide what to do, the camera is placed inside of the closet looking out at them, clothes obscuring the top of the frame.

Only when they are sure that they are alone and unwatched do we typically see them in close-ups and more intimate shot coverage.

Su and Chow spend the movie asking themselves how their spouses could have ended up together in their illicit affair. To figure this out, they decide to roleplay the scenes that they think could’ve led their spouses to become intimate with one another, and they wonder which of the two started the affair in the first place.

Writer / director Wong Kar-Wai poses his answer to this question in two back-to-back versions of the same scene early on in the movie. Su and Chow roleplay the “first flirtation” as they walk home down an alleyway at night. In the first version of this scene, he makes the first move. In the second, she does. With this juxtaposition of the nearly identical back-to-back scenarios, it becomes clear: it doesn’t matter. It takes two to tango.

Su and Chow recreate the “first date” at a restaurant. They order food for each other, picking what they think their spouses would’ve ordered. They end up eating the same dish.

Later, they spend all of their free time together. They call each other at work. They stand outside in the rain and talk. Chow books a hotel room for them at the far end of a hallway draped in passionate red. There, they only talk… about their spouses, and their own shared interests.

The first time that Su leaves the hotel room and walks down that passionate, red hallway, she tells Chow “We won’t be like them.” But she only walks a few paces before she pauses. What if…

Su and Chow never consummate their relationship, but over time, they realize a simple, uniquely painful truth: “Feelings can creep up just like that. I thought I was in control. But I hate to think of your husband coming home.”

Su and Chow fall in love, but they do not act on it. Soon, he is relocated to Singapore for work. She maintains the status quo and stays with her husband. They both desire to be together but lack the courage to pursue it. In the end, they are haunted by what could’ve been.

The Hong Kong in In the Mood for Love is suffocating, a match for those strangled emotions. Su works as her boss’ secretary and sits directly beside his desk. The couples live next door to one another in a cramped apartment building, with a nosy landlord who constantly crosses personal boundaries and inquires about where they are going at all hours of the day. It is often raining, making it impractical to spend time together outside, even shrouded in the dark alleyways.

The film ends with missed connections: she visits his apartment in Singapore and leaves behind a cigarette with a lipstick stain; he visits the apartment complex in which they met… and, not knowing if she lives there anymore, stares at her apartment door, not daring to knock.

Su and Chow never reveal their relationship to anyone. They hold on to their secret love for the rest of their lives. Wong Kar-Wai plays this not as melancholic, but empathetic; it isn’t a sad symphony that we hear as Su and Chow exchange an intimate stare in slow motion in the dark alley, but a waltz.